As-Built Documents: Preserving the Past to Improve the Present

As-Built Documents: Preserving the Past to Improve the Present

In the early 2000s, owners and designers of The Dalles Dam, which spans nearly 1.7 miles between Washington and Oregon, undertook a $20 million improvement project. Upon beginning the project, engineers discovered outdated as-built drawings – a result of an industry-wide reduction of record-keeper positions in the late 1900s – that impeded the new project’s design.

In the world of construction and development, as-built drawings are key to future success and risk avoidance. Accurate and thorough archives of changes made over time to original work enable future owners, engineers, designers, and mapping professionals to build on the legacy of those before them.

The Dalles Dam is just one of many U.S. projects in recent years that have been hindered by inaccurate or incomplete documentation of prior work, leading to delayed schedules, blown budgets and, in many cases, facility damage. Once a legacy of surveyors, engineers and designers, the proper retention and updating of archives has fallen out of favor.

Particularly with underground facilities, the legacy and strong commitment to continuously updating archives passed down by the surveyors, engineers and designers of a time past, have not been sustained. Ironically, the industry collectively knows more about pipelines and underground infrastructure built 100 years ago than more recent work.

Groundbreaking Practices

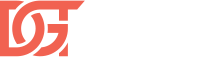

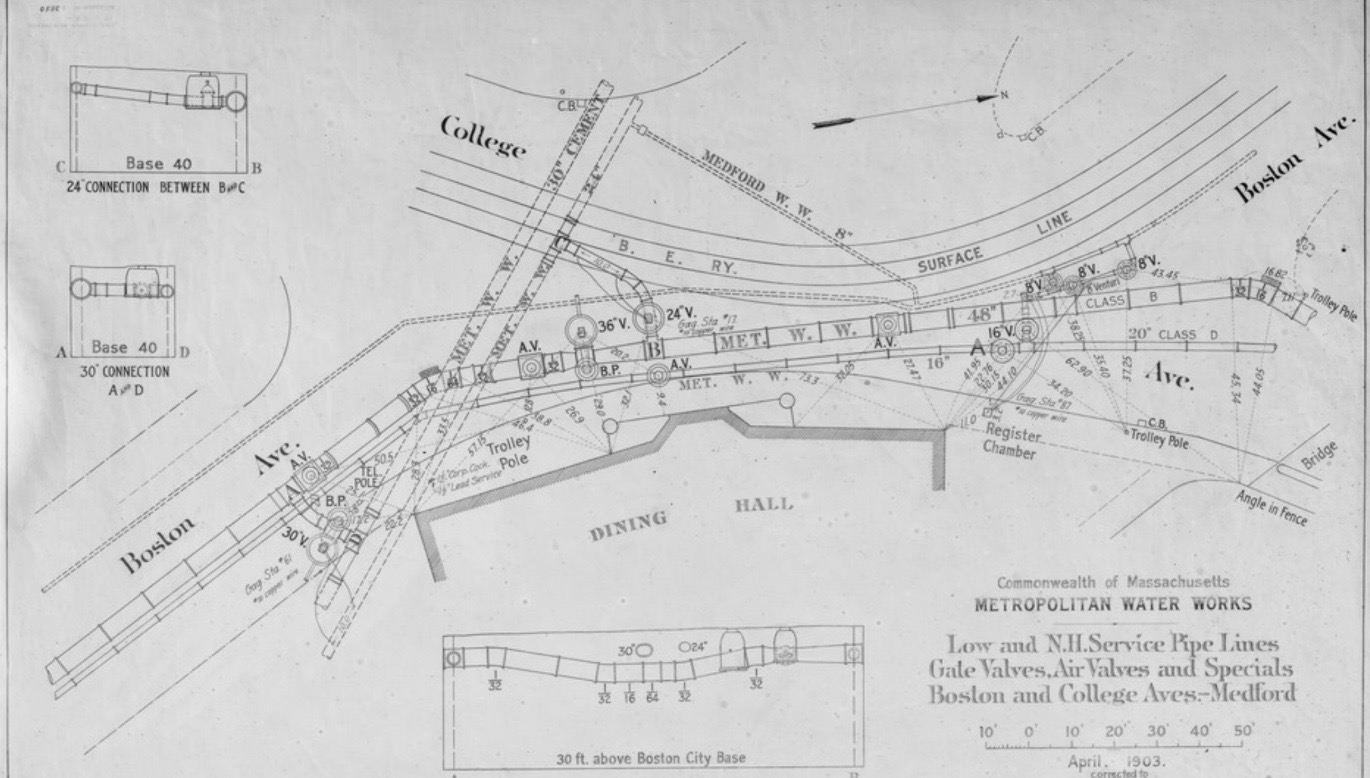

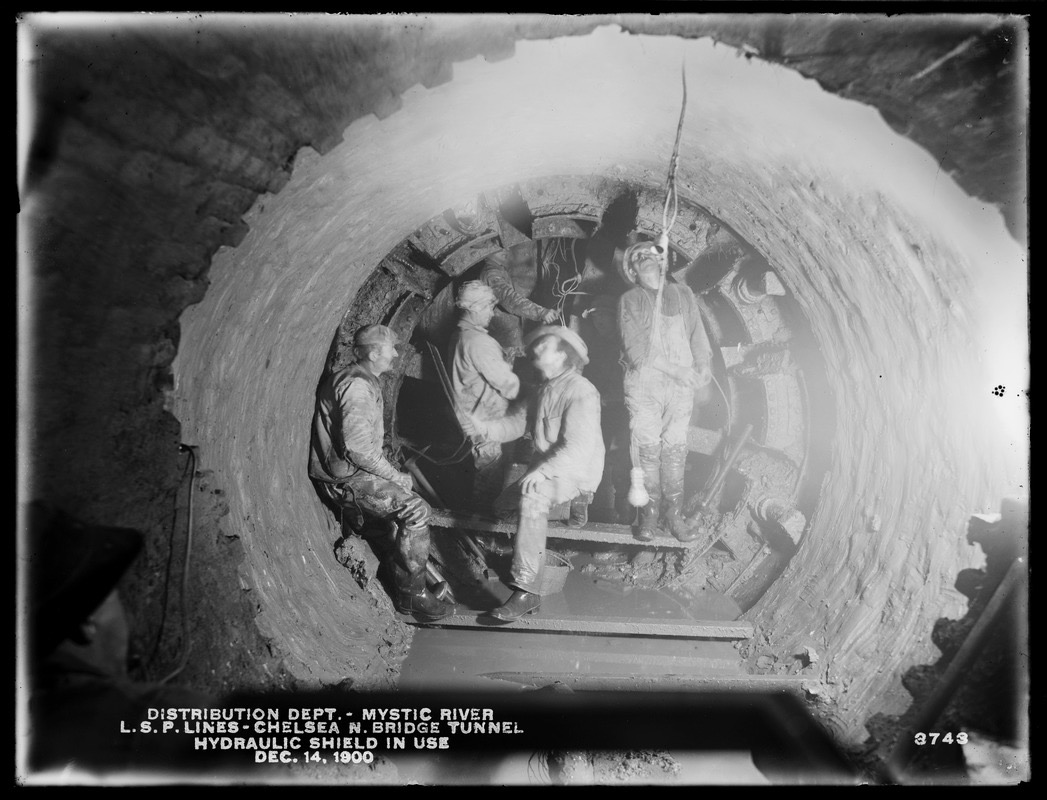

Finite land resources dictate that development be an iterative process, with parcels and properties being reused and rebuilt as societal needs evolve. In the late 1800s, there was an enormous investment in building, expanding and replacing older facilities, particularly in New England. A population boom necessitated investment in mega infrastructure projects such as reservoirs, long distance water and sewer transmissions systems, and even underground tunnels for electrified subways. Without any of the large equipment in use today, the work was done by thousands of workers, armed with little more than picks, shovels, rock breakers and hoists. They dug, burrowed and fought their way through rock and mud to build our vital infrastructure.

The novelty of this sort of work coupled with the risk involved led to meticulous documentation and a desire for perfection in project design. For example, legacy documents show that designers who were tasked with building Boston’s underground transit system traveled to Europe to meet the designers behind other subways, and returned with insights on how to properly document and overcome challenges in construction.

The early professionals did not rush projects through design into construction, despite the urgency of rapidly growing cities. Decision makers of the time thoroughly documented the design and construction details, and the drawings left in today’s archives are a testament to their efforts. In New England, many of the facilities built in the early 20th century or before are still in use today, thanks in large part to accurate as-built documents that facilitate renovation and improvement instead of demolition and reconstruction.

Despite New Tech, a Troubling Lack of Commitment

One-hundred years later owners, engineers, designers, mapping professionals continue a tradition of refurbishing, rebuilding and expanding facilities to meet the same demands of growing populations. With more people moving to urban areas, we are again building and constructing at a feverish rate – now, with high-tech tools.

Mobile scanners allow for faster data collection; drones make it more feasible to work in hard-to-reach areas; virtual reality enables real-life depictions of sites and designs. Using 3D laser scans, Building Information Modeling (BIM) data is converted to design, build and capture precise details of new construction, which aids in the maintenance of structures through their entire lifecycle. With these tools, details embedded in the ceilings, floors, and walls can be inspected by future generations. Indoors, the tradition of strong construction recordkeeping is alive and well.

By contrast, the as-built records of facilities built beneath our feet may not have the same detail. In a recent report, the cost of replacing one mile of electrical distribution lines in New York City was estimated to be more than $8 million. A large part of the cost is due to the complexity and risk of working in crowded utility corridors, relocating other utilities and contingency bidding for surprise discoveries underground. With more work being done under our streets to bury utility lines and other infrastructure, and eroding commitment to adequate as-built documentation, the cost of working and building underground will continue to skyrocket.

Projects like the Dalles Dam demonstrate that a commitment to as-built documentation of construction and development – especially underground work – for future generations of workers is lacking in many current projects. Despite the new technology available on job sites today, the industry often fails to adequately capture details for future generations to visualize our work.

What our forefathers understood in the late 1800s is that a successful project was not just a job done on time and within budget, but a job that was also well-documented in order to maintain the places where we live and work. They knew that documenting their work was important – for pride, for posterity, and for the promise of future work done right.