Lessons Learned from Boston’s Underground Revolution

Lessons Learned from Boston’s Underground Revolution

Boston is currently one of the most desirable United States cities to live and work, consistently ranking high in categories like quality of life, job market, sports, green space and parks, political scene, and culture. As one of the oldest American cities and the site of many important events during the country’s founding, the city’s rich history gives it an obvious allure. But the richness of Boston’s history and culture isn’t limited to what can be found above ground; it’s also buried beneath our feet.

Unbeknownst to many locals and transplants alike, Boston has a long and illustrious history within its infrastructure. In 1897, Boston built the first underground subway system in the U.S., and one of the very first electrified systems in the world. Boston’s advanced underground transit system modeled for New York and other modernizing cities a way to successfully advance transportation and infrastructure with minimal disturbance to aboveground life. Even today, many of the large infrastructure projects completed between the late 1890’s and the late 1920’s in Massachusetts are still in use, providing vital energy, communication, water, and transportation systems for our growing communities.

The preservation of this infrastructure and insights gleaned from the practices used to create it can provide us with valuable lessons in how to continue standards of excellence in major development.

Answers in the Archives

Just as Boston’s infrastructure has been preserved, so have many of the development drawings, archives, and prints from a forgotten era. While many cities commonly face missing or damaged documentation from vintage projects, Boston boasts a wealth of legacy documents that chronicle the ingenuity, hard work and focus of the forefathers of development, engineering, and surveying.

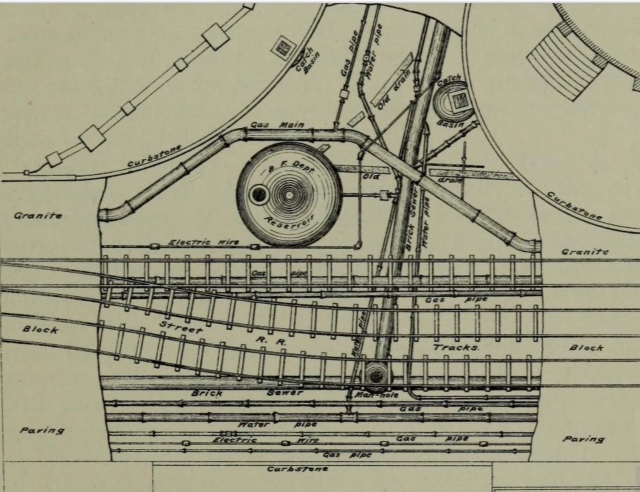

In some of the earliest examples of subsurface engineering we have, Boston engineers, designers and constructors working on the 1890s subway system collaborated on subsurface investigations to uncover complex and aging facilities. Insights from the Boston Transit Commission’s reports illustrate just how important it was for the team to understand the existing site conditions before completing the final design.

For example, preserved reports and documents reveal that the subway tunnel design incorporated the survey position of the streets, buildings, foundation elements, and even the gravesites of the dead. This level of detail and care helped planners accurately imagine the design of the new underground world in concurrence with the built environment of the time – an approach that remains crucial to usable, foundational surveying today.

A Digital Revolution in Record Keeping

In modern development, some of the surveying principles established by the industry pioneers of the 1890s have been lost. One of the great challenges faced today in subsurface utility mapping and underground damage prevention programs is the lack of reliable, accurate data on which we can base project planning for subsurface investigations. The consequences of that go beyond delays and inconvenience – reports from the Common Ground Alliance reveal that underground excavation damages in the U.S. rose by 20% between 2016 and 2017 costing stakeholders at least $1.5 billion.

Unfortunately, even a city as historically inclined as Boston still left some of its early surveying and engineering principles in the 19th century. The process of planning underground utility relocation for The Big Dig project revealed that years of as-built drawings from contractors for a significant amount of the 29-mile stretch of utility lines were missing, incomplete, or inaccurate.

Fortunately, there is good news. In recent years, advancements in survey and mapping instruments such as GPS-enabled devices have enabled the digital documentation of new works by non-survey-based professionals such as engineers, inspectors, and contractors. Further advancements in digital storage mean we can accomplish better, more thorough record keeping as well. Building information modeling (BIM) technology widely-used by managers today for 3D documentation of building projects can also be applied to underground environments.

As decision-makers, owners, designers, and constructors move forward in their development projects, principles from the 1800s still ring true of holding accurate documentation in high esteem. With a legacy reaching back 125 years, our perspective at DGT is grounded in experience, and that experience tells us that best practices often involve blending traditional and established principles with innovative thinking.

When considering what should be the best practices of today’s subsurface investigations, DGT considers that the guidebook has already been written, and even if some of it has been forgotten, we can still take the steps needed to make sure we combine past with present to create a better future.