The Land Hiding in Plain Sight: An Answer to Boston’s Affordable Housing Crisis

The Land Hiding in Plain Sight: An Answer to Boston’s Affordable Housing Crisis

Across the nation, home prices and the cost of rent surpassed historic records in 2022. The majority of housing markets experienced significant price appreciation—between a 50% and 100% increase—over the past two decades. While housing costs continue to climb, wage gains have stagnated, leaving millions of Americans struggling to find affordable housing. This spring, the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC) released its latest report, The Gap: A Shortage of Affordable Homes, citing, “no state has an adequate supply of affordable rental housing for the lowest income renters.” The data revealed a nationwide shortage of approximately seven million affordable rental units, resulting in only 36 homes available for every 100 low-income renter households.

As one of the oldest cities in the country, Boston has experienced its share of developmental, economic, and population booms. Although, growth has not benefited all residents equally, especially in the housing market. In 2018, median values were up to 48% higher than their previous peak, building a barrier to homeownership for renters. Nearly 65% of Boston residents are renters and more than half spend 30% or more of their income on housing. As of August 2022, Boston residents paid an average of $4,563 per month for rent, the third highest in the country. At this rate, living in Boston is becoming too expensive for the working and middle classes. Addressing the affordable housing crisis is long past due.

On the Lookout for Vacant Land

After her election victory in late 2021, Boston Mayor Michelle Wu promised to prioritize housing affordability and stability for local families. Mayor Wu strongly believes that safe, healthy, affordable housing is a human right and she’s putting money where her mouth is—Wu announced $40 million to fund new affordable housing units across the city. Of course, to create more affordable housing, the city needs land to build on, and with a high population density, and opportunity for more growth, locating vacant land in Boston seems like finding a needle in a haystack.

In response to Wu’s ambitious vision of housing justice, the City of Boston performed a Citywide Land Audit to create an inventory of all city-owned property. The team of advisors set forth to gather data from multiple sources to identify all land parcels and buildings that are vacant or underutilized. Wu planned to use results to make data-driven decisions about how to deploy public land to serve Boston’s most urgent needs like affordable housing. Utilizing city-owned land avoids paying the steep price of new land and could make it attainable to create affordable housing. If Wu can progress her plan to solve the housing shortage, Boston could be at a critical turning point.

Public Land for Public Good: Citywide Land Audit. Boston Planning & Development Agency. (2022). https://www.boston.gov/sites/default/files/file/2022/06/2022-CityLandAuditReport_Final%20(3).pdf

Public Property for Public Good

When the audit results were released in June 2022, the report disclosed that the city controls 176.9 million total square feet of real estate made up of 2,976 unique parcels of land, and 1,238 of the parcels (9.5 million square feet) are vacant. Although it sounds like the city has plenty of free space, most of the open lots are only appropriate for small housing developments, not for large multi-family or mixed-use development. But, there may be a light at the end of the tunnel—as of May 2022, 28% of the vacant parcels were undergoing development, and another 42% were identified as potential future projects. In Roxbury, one long-awaited project is underway, which will result in significant lab space and affordable housing units. When bidding for the land, the development team claimed, “Our entire approach to the project was devised to create the greatest number of the most deeply affordable units as possible, and the land value generated by the life sciences buildings will create a cross-subsidy that will supplement public funding sources.”

While about 9% of vacant parcels still don’t have development plans in motion, there’s a great deal of potential. Through the land audit analysis, the city identified types of available sites that are appropriate to use for new affordable housing. Excluding vacant land that is reserved for open space, such as parks, the portfolio includes the reuse or redevelopment of vacant municipal buildings, infill housing sites, increased density at active municipal sites, and parking lot conversions. A few of the key sites identified include:

Boston Public Health Commission Campus, Mattapan: The BPHC Mattapan Campus is a sprawling property currently serving several populations, including seniors, children, and residents in recovery. There are two buildings on the grounds that are ready to be demolished and could be rebuilt with the specific use for supportive housing.

While about 9% of vacant parcels still don’t have development plans in motion, there’s a great deal of

A-7 Police Station, East Boston: Due to the construction of a new A-7 Police Station, the soon-to-be vacant A-7 Police Station presents an opportunity to continue using an otherwise unused public asset for supportive housing.

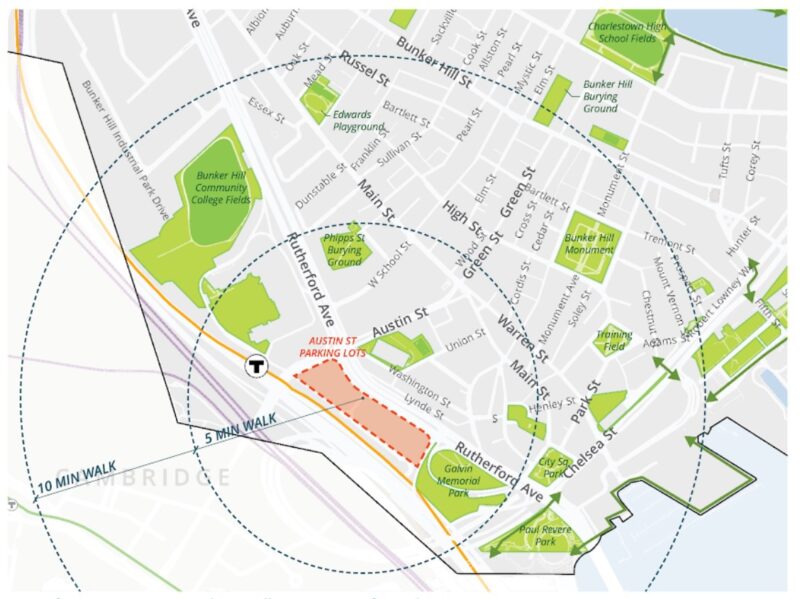

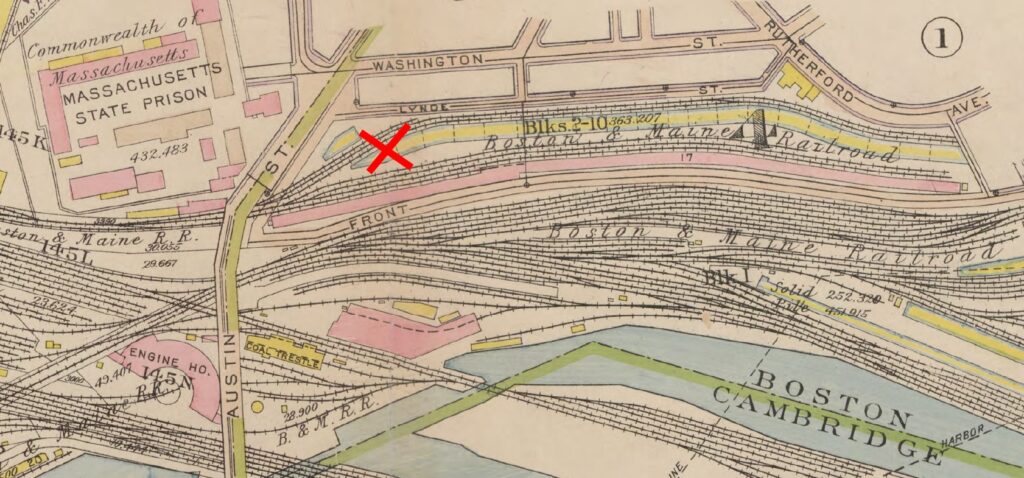

Bunker Hill Community College Parking Lots, Charlestown: This 216,172 square foot site, situated at the major northern gateway to Central Boston, is currently used as parking for the abutting Bunker Hill Community College in Charlestown. Originally developed as rail yards for the Boston and Maine Railroad, the site has been drastically changed in the automobile age, with the re-alignment of the Rutherford Avenue thoroughfare, and parcels were carved into their current configuration in the 1990s Central Artery/Tunnel project.

In Support of Surveying Future Homes

As local residents and leaders in the surveying industry, the DGT team are advocates for Mayor Wu’s efforts to take advantage of the city’s underutilized land to increase homeownership and renting opportunities for Boston’s working class. In fact, we’ve partnered with Boston Planning & Development Agency (BPDA) to survey land as potential affordable housing sites. At DGT, we’re proud to be involved in the process of examining and mapping land that deserving Boston residents will eventually call “home.”

To date, we’ve performed thorough, up-to-date surveys of the Charlestown and Mattapan sites under their Master Services Agreement with the BPDA. The Mattapan site, with its “country in the city” feel, holds particular meaning for DGT’s surveyors. Two decades ago, DGT provided extensive land surveying work to support the development of the current Mattapan Heights housing, previously the Boston Sanatorium. Both recent surveys included a Subsurface Utility Investigation of these much worked-over areas, where critical lines in the local utility infrastructure cross over.

The Lasting Impact of Land

Solving the current housing crisis is a major undertaking that requires a long-term strategy, and many changes are required to meet the current demands for housing in Boston. But utilizing uninhibited land and repurposing vacant structures is a solid starting point. Other cities, including Philadelphia and Sacramento, have proven that transforming publicly owned land and buildings to affordable housing can help a community thrive.

While providing net new housing is a deep-rooted plan, progress can be made in the short term, too—for example, Mayor Wu is working to lift the ban on rent control and expand emergency housing options. At DGT, we’re in it for the long-haul, and look forward to being involved with the re-purposing of the important crossroads in historic Charlestown and Mattapan, and many more projects to come.

Learn more about our surveying and SUE/SUM service offerings.