From Marking to Mapping Blog Series

Improving Upon Our Dig Laws: Recognizing Inadequacies

Improving Upon Our Dig Laws: Recognizing Inadequacies

It Starts at Home: The Need for Better Dig Safe Laws at State and Local Levels

It has become far too common to hear about the striking of an underground utility line—a hazard invisible from the ground above. Across the United States, millions of miles of pipelines lie directly under our feet, providing essential services that fuel all aspects of life, from gas lines, water pipes, electrical lines, sewer systems, communication cables, and much more. Accidental strikes of underground facilities interrupt essential services, cause financial implications, result in serious injuries, and in some cases, loss of life.

According to the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) 20 Year Trend Incident Report, there were 1,183 pipeline-related injuries and 281 fatalities between 2000-2019. These incidents also account for approximately $10 billion in property damage and this does not include the local, unreported incidents that claimed many more lives.

Though national organizations, such as the Common Ground Alliance (CGA), help to enforce best practices and instill safety within the industry, there are many untapped solutions and inefficiencies that continue to put lives at risk. In an effort to improve project outcomes, and more importantly save lives, we must drill down to the regulations at the state and local levels, and ask ourselves: do the laws in place go far enough to protect critical infrastructure and human life? Is there enough enforcement and accountability for those that cause these incidents? At DGT, we think it’s time for a change.

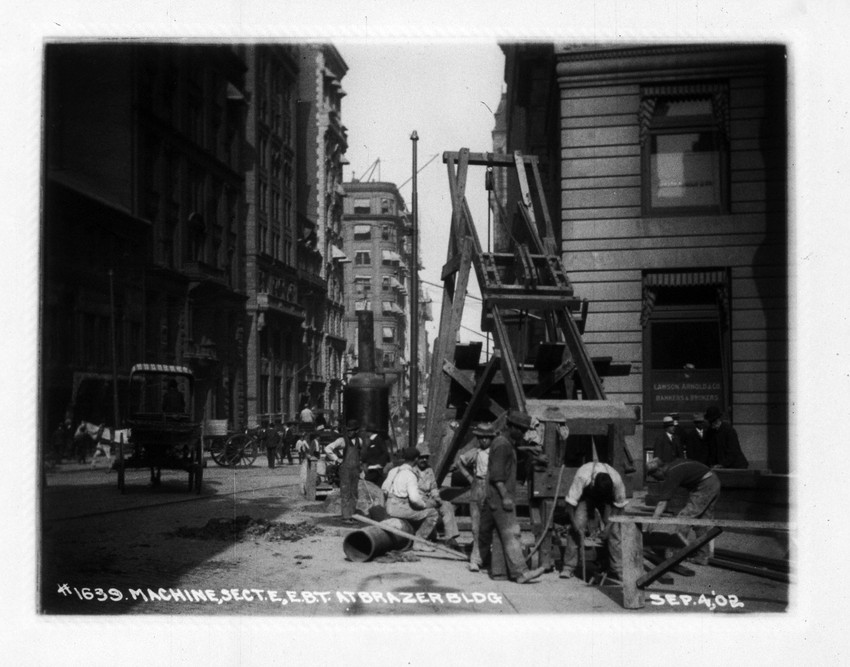

History of Damage Prevention

In 1969, a natural gas explosion occurred in Culver City, California, which claimed the lives of four and injured countless more. The cause of the pipeline disaster—inadequate subsurface investigation. Due to inadequate paint markings, the crew was not aware that below the surface lie a petroleum pipeline. Webster B. Todd, Jr., chairman of the National Transportation Safety Board, stated that investigations had revealed “that someone was 18 inches wrong.” He added, “Someone should make damn certain exactly where that pipeline is located. You don’t just fool around in a situation like that.” This incident brought to light the inefficiencies within the safety and damage prevention industry, and out of the ashes of this terrible event arose a commitment to prevent future disasters.

The Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA 21) was passed by Congress in 1989. In this legislation, the US Department of Transportation (USDOT) was required to conduct a study identifying and validating the success of existing best practices, and ways to enhance worker and public safety during excavation activities. Underground alliance leaders quickly realized that this gathering, facilitated by the government, provided them with a unique opportunity to improve their industries for future generations. The resulting study became known as “The Common Ground Study.”

During this effort, 162 individuals took part in the study and identified 130 best practices to enhance safety and prevent damages to underground facilities. After 11 months, the results of their discussions, referred to as “best practices,” were submitted to the Secretary of Transportation. Following their submission, it was determined that these best practices should be continuously improved on as technologies advanced and information evolved. In 2000, the unified group was formally established as the “Common Ground Alliance” to further the work completed during the Common Ground Study.

High Notes in Damage Prevention

Since the CGA’s establishment, the group has been involved in creating and implementing safe and reliable operation, maintenance, construction, and protection practices for underground facilities. Composed of 16 industry stakeholder groups, the CGA meets once a year to discuss, review, and update industry “Best Practices.” This resource is released every spring to reflect changes and updates in technology, as well as relevant industry trends. Through this document, the CGA establishes an even playing field for all industry leaders.

The CGA launched another achievement: the 811 public awareness campaign. The 811-phone number is now a nationwide toll-free number designated by the Federal Communications Commission that connects professionals and homeowners who plan to dig with their local one-call center. The 811 campaign provided an easy number to remember and an effective slogan—“Call Before You Dig.” The CGA also heightened the effectiveness behind the campaign by including high-profile sports sponsorships, billboards, and even designated August 11th (8/11) as National Safe Digging Day.

In 2003, the CGA took another step forward and launched the Damage Information Reporting Tool (DIRT). This tool allows stakeholders to submit underground damage and near-miss incidents through an online web application. The goal of the DIRT report is to enhance underground damage prevention education and training efforts, and to target specific points of best practice improvement.

However, as we reflect on the success of the DIRT report, we must also address the clear pitfall—this report is voluntary, not mandatory. DIRT reports clearly attribute the root cause of many utility strikes to excavators skipping one-call ticket requests. Without mandatory reporting laws in place, it’s impossible to gather meaningful data on the total number of underground facility events. Expanding reporting efforts will allow for a comprehensive and accurate data set and will help the industry uncover their pitfalls.

The CGA has built a foundation with its many efforts. But now, the onus lies on individual state responsibility to implement laws and regulations that mandate reporting and go beyond one-calls.

Imperfect Processes

While the efficiencies displayed by the CGA paint a picture of success, there is more work to do to improve best practices, industry training, and state and federal regulations. Under the current damage prevention system, the contractor or homeowner calls their local one-call center 48 to 72 hours prior to excavation, depending on the state. Next, the one-call center notifies any utility operators that have facilities near the requested dig site. Following the notification, the utility operators then mark the site, or dispatch their locating contractor, with paint or flags to signify the location of a utility. Finally, the excavator is able to break ground.

While this system worked well decades ago, there is no reason in our digital age that urban hieroglyphics should still be the main source of communication between the utility companies and contractors. The latest advancements in remote sensing technologies allow us to efficiently map above ground and below ground with immense accuracy, giving stakeholders a thorough understanding of site conditions prior to breaking ground. This begs the question: if advanced subsurface mapping technologies exist, then why are we still relying on paint markings on the ground?

Enforcing Best Practices at the State Level

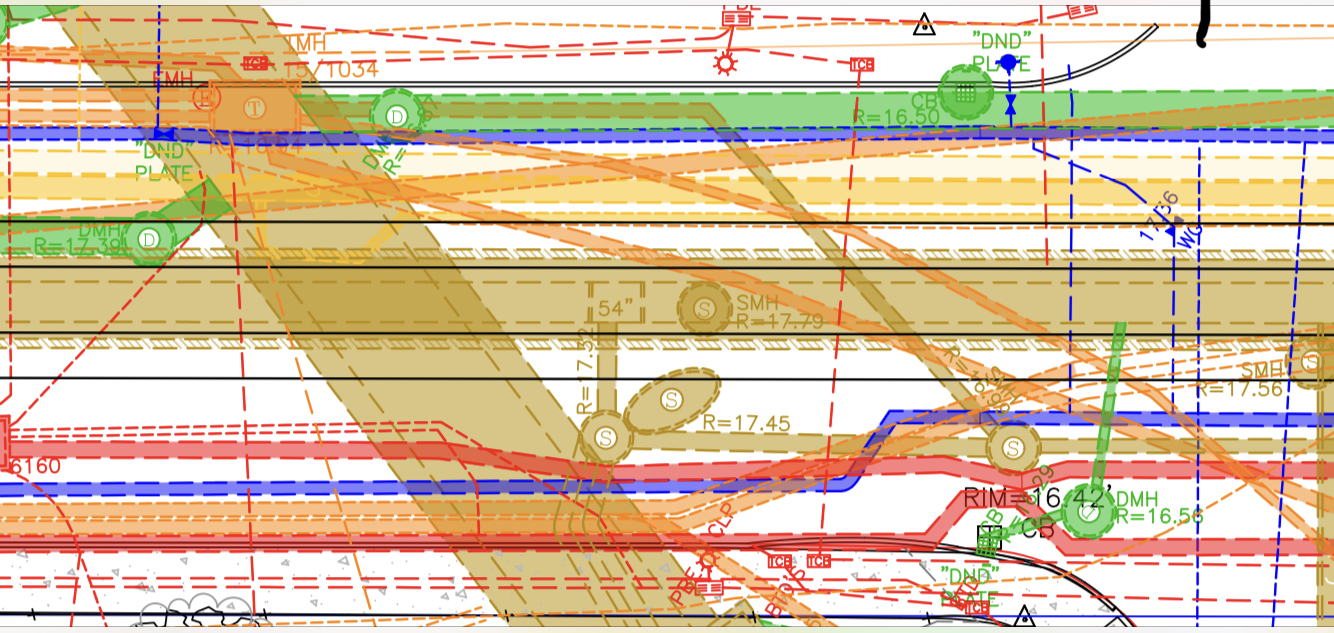

Two states—Pennsylvania and Colorado—realized the need for improvement and implemented laws and regulations that mandate subsurface utility mapping prior to digging. Pennsylvania’s One Call Law Act 287, Section 6.1 states that it is the duty of each project owner who engages in excavation to utilize subsurface utility engineering (SUE) to determine the existence and positions of underground facilities.

When SUE is applied properly during the design phase, there are significant cost and damage-avoidance benefits because the information can be shared with all parties and utilized on site. If SUE was a mandatory best practice prior to digging, excavators on site would be able to compare what they see on their tablet, with what is happening in real-time. Every state should follow the lead of Pennsylvania and Colorado and implement subsurface utility mapping laws.

Further, states must do a better job of enforcing the laws. Currently, there is a lack of enforcement within the one-call system which is allowing for chronic harm. In some cases, corrupt companies create damage, pay their fines, dissolve their company and start a new company under a different name following the same corrupt practices. When this happens, one-call centers are unable to determine if it’s the same company under a new name. In other instances, contractors file for a one-call ticket but proceed with digging prior to having technicians mark pipeline locations.

In a recent case in Sun Prairie Wisconsin, workers struck an underground gas line. The cause of this explosion—digging without proper site markings and with an expired ticket. This explosion flattened buildings, damaged a section of the city’s downtown, and claimed the life of a first responder. One of the parties responsible for the deadly incident later acknowledged to the Wisconsin Public Service Commission, which regulates public utilities, that he knowingly violated state law by digging with an expired ticket. Nearly two years later, this same company has yet to pay the $25,000 fine, has not attended the required $100 education course, and is reportedly back in Wisconsin working under a new name. This incident displays the clear flaws displayed within the system. To prevent these tragedies, states need to update regulations and do a better job of enforcing best practices. Too often tragedy marks the time of change, it’s time to be proactive.

Damage Prevention Tools and Technologies

Until two decades ago, there was no way of creating a 3D model of the underground infrastructure. Since then, the industry has seen a dramatic technological evolution. Remote sensing devices help trace the path of buried facilities without having to unearth them. GPS and terrestrial LiDAR systems are able to generate precise, three-dimensional information about what lies below the surface. It’s time these tools become mandatory in the field, not optional.

A new technology entering the market, wearable mobile mapping created by NavVis, has the ability to not only collect enormous amounts of spatial data but also hold asset owners and excavators accountable for mistakes. When a line is struck, it’s common for both utility companies and excavators to point the finger at each other. A 2004 gas pipeline explosion in Walnut Creek, California, demonstrated this tension. While the line owner, an energy company, said the line was clearly marked, the excavators had a different story. With just paint left on the ground, determining who’s at fault becomes challenging.

NavVis has developed a wearable mobile mapping system that, similar to traditional mobile mapping, scans your surroundings. Each scan is then stitched together to form a complete picture of your site—paint markings and all. If a line was struck after being scanned with this technology, there would be irrefutable evidence as to who is at fault. Utilizing technological advancements, like NavVis, would create a safer and more accountable work site.

Having seen the evolution of these practices during his decades in the industry, Michael Clifford, Co-founder and Principal at DGT added, “In order to build a stronger damage prevention program all parties, state and federal government and the CGA, must work together to set new rules and enforce them. Increasing technology in the field, enforcing best practices, and enhancing the communication between asset owners and contractors will go a long way in preventing harm and improving the industry.”

This article is part of a series “From Marking to Mapping,” in which DGT shares our view on best practices for locating, mapping and ultimately protecting underground utilities. Check out the first blog in our series titled, “Urban Hieroglyphics: The Shortcomings of Paint and Mark-outs in Utility Mapping.”