Why the Future of Development in Boston is Looking Up

Why the Future of Development in Boston is Looking Up

The one constant element of Boston over the last few decades has been change. According to a recent article on Boston.com, “on any given day in Boston there are more than 100 large construction sites within the city limits.”

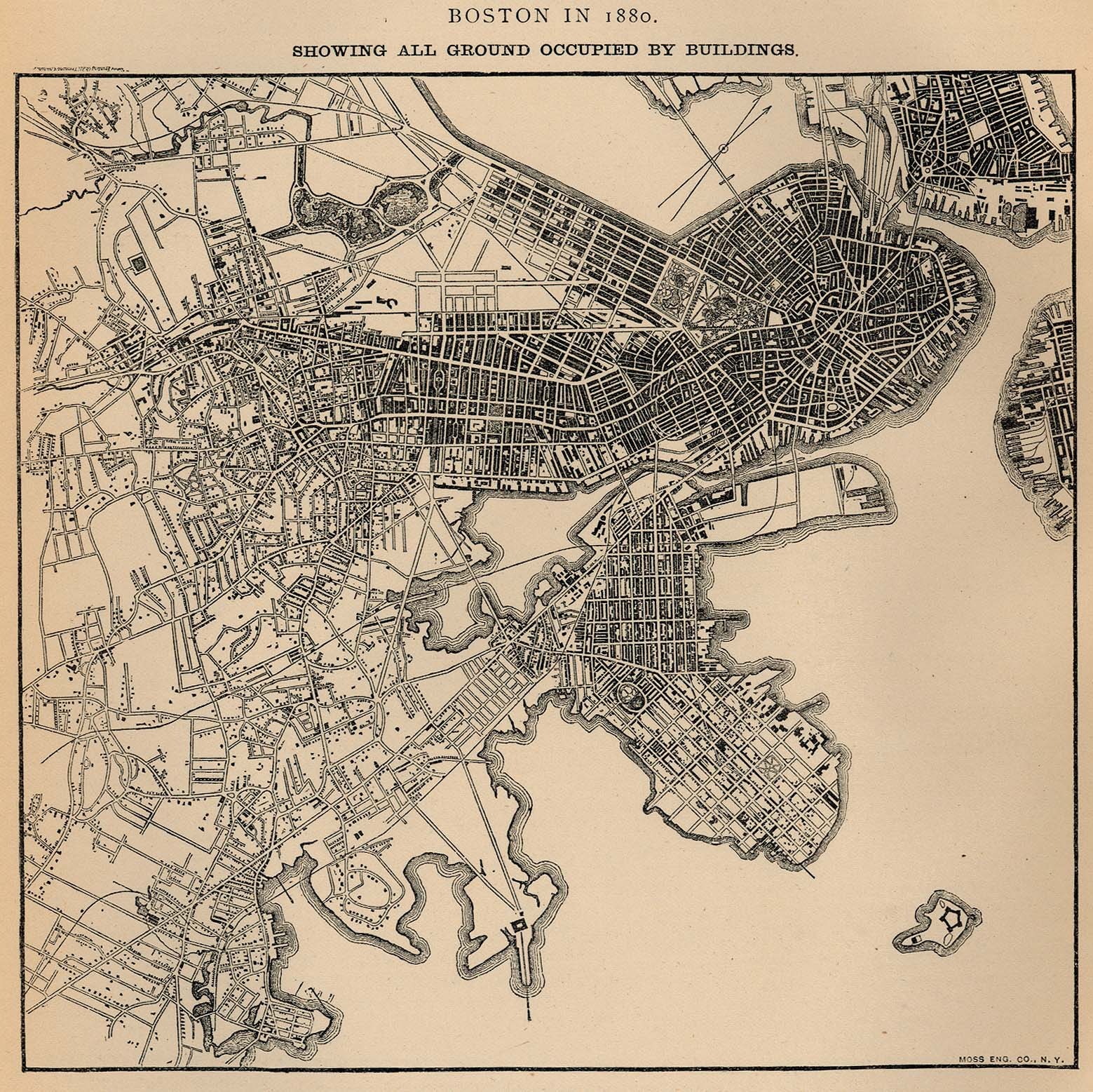

The city skyline of today barely resembles that of 10 years ago, let alone that of the 20th century. Boston, more than most American cities, has gone through astounding physical changes through land creation – what the historian Walter Muir Whitehill called its “topographic history.” The change is so radical that the Puritans of old would not be able tell present-day the North End from the South Bay – especially since the South Bay was under water when the area’s first British visitors arrived.

Boston’s development changes began with the “wharfing out” of the tide-bound Shawmut Peninsula from the Colonial period into the 19th Century, which can be attributed to the Puritans and the Colonial Ordinances of 1641-1647, a precursor to the Massachusetts General Court’s passage in 1866 of Chapter 91 (also known as the Public Waterfront Act).

Major filling of tidelands ended with the mid-20th Century extension of Logan Airport and the South Boston Piers into Boston Inner Harbor, which was timed with the post-war end of Boston’s extended economic doldrums and the development of the “High Spine” of high-rises extending along the Mass Pike Extension into the heart of the city.

The city’s changes were not all limited to Boston proper. The outlying districts, the annexed former towns of Roxbury, Brighton, East Boston, and others – as well as smaller nearby cities like Cambridge and Everett – transformed from former farming communities with manufacturing villages into “streetcar suburbs” packed with three-family houses sending commuters into the expanding downtown.

From Bay to Bustle

Although the city proper’s population has only grown from about 572,000 in 1990 to just under 700,000 now, the Greater Boston surrounding area has become the nation’s 10th most populous metropolitan area. As a result of that growth, the face of the city has changed. The Seaport District on the harbor, once a mostly empty area dominated by shipping facilities, is now buzzing with nightlife and tall, modern buildings full of office and living spaces. The “High Spine” seems to add new skyscraping vertebrae each year.

It may appear to some longtime residents that Boston is undergoing change it has never seen before. Yet the current expansion is not unprecedented. Boston’s residential population peaked two generations ago in 1960 with almost 700,000 people residing in the city. The 2018 census data estimates Boston’s population to be approaching the peak at 694,583.

Practically speaking, there is little room left for buildings from a horizontal view. Now that the Seaport has filled in with offices, retail, and living spaces, there are not many open plots of land across the city for brand-new development – unless we want to start paving over the Common and other purposeful green spaces.

The basic principle of real estate development: landowners are compelled to convert their land to its “best and highest use.” What this means in land-scarce, 21st-century Boston is that many of the humble one-story buildings throughout the city that provide neighborhood convenience and blue-collar jobs – corner variety stores, laundromats, mom-and-pop bakeries, machine shops, warehouses, and others – will slowly begin to disappear. Add to this the steady development of new apartment buildings city-wide, and we now see a true change in the visual landscape of the city.

Going Up Instead of Out

A few generations ago, Boston was in effect two cities: the glittering Downtown and the family-oriented neighborhoods beyond. Now, we see high-rise mixed-use buildings where office and retail space sits below luxury condos and apartments. Bostonians live where they work and work where they live, and developers continue to stack buildings into the sky.

There are benefits and drawbacks to Boston’s upward growth. The city has the country’s 19th highest population density at nearly 14,000 people per square mile, yet its landmass, at just over 48 square miles, is 221st in size. With nowhere to go horizontally, the city’s vertical expansion represents its best bet for economic benefit, through taxes and other revenues.

On the other hand, every towering building that shoots into the sky seemingly overnight often means the disappearance of an old piece of Boston that will never return. The houses and small shops that were a staple of Boston’s tight-knit residential neighborhoods may soon become obsolete as multi-story residential towers continue to proliferate. The history and memories tied up in what Boston used to be will begin to fade under the bright lights and shiny new buildings that make up what the city is becoming.

Nearly 400 years since Boston planners figured out how to use landfill to expand the tiny, waterlogged Shawmut Peninsula into a city with many districts and neighborhoods, the changes have only continued to roll in for the City on a Hill. The difference now is that when we talk about development in Boston, we no longer look at open space on the ground. Instead, we look to the the open space above it.