The Surveyor: A Guardian of Wealth

The Surveyor: A Guardian of Wealth

On April 21, 1898, an article in the New York Herald observed, “It is an astonishing thing that men will fight harder for $500 worth of land than they will for $10,000 in money.”

The next day, thousands of people frantically raced across an Oklahoma plain in what became known as the Oklahoma Land Rush.

Throughout history, the most steadfast and universal measure of wealth has been the ownership of land. As the renowned 20th-century real estate magnate Louis Glickman said, “The best investment on earth is earth.”

The value of that investment is predicated, as with all treasures, on an exact measure of how much land one owns, which requires the work of a highly trained professional. At the heart of the land surveying profession in the United States is the surveyor’s role in protecting property rights for both private and public purposes. The licensed land surveyor’s duty is singular in determining lines of ownership, easements, rights of way and other human uses of the ground beneath our feet.

Professional surveyors carry a workload that greatly exceeds simply laying down tape and checking distances. They are also expected to be able to interpret legal documents, maps, plans and previous survey reports to interpret what those measurements mean. They may not practice law, but in order to be truly helpful to those who do, they must understand how the courts decide on boundary disputes, knowing that a monument or a natural feature may take precedent over years of seemingly authoritative documents. Many surveyors even continue their education by taking law classes in order to be conversant when consulting with attorneys and other land use professionals.

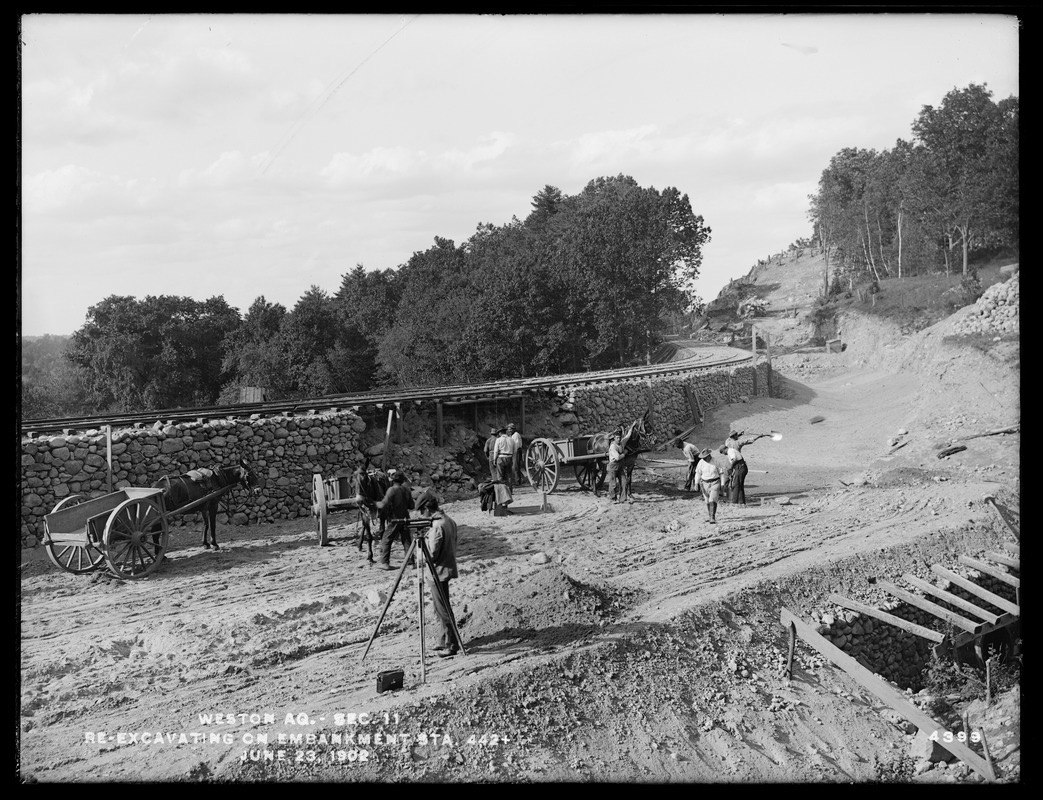

One of the key challenges in modern surveying is reconciling old records with modern methods. We frequently hear from clients who have surveys from the 19th and early-20th centuries, which were performed using outdated methods like chains, builder rods and tape. Those tools and methods have been relied upon for centuries, even dating back to surveying’s infancy in ancient Egypt – and in some cases the industry still uses them – but modern technology provides precision that the old methods simply cannot match. A 100-year-old survey that has been used as a primary source for residential or commercial property development may turn out to be inaccurate. It’s up to a qualified, professional, and licensed surveyor to know.

Our work as surveyors has value beyond the technical work to perform measurements. That value should be apparent to us and to our clients, yet many in the surveying field will dramatically reduce their fees in order to outbid competitors, or simply because they enjoy the work so much that they’ll take smaller fees just to have more to do.

Worse, the value of a competent professional surveyor is often undercut by those who do sloppy work, cutting corners while representing themselves as fully qualified simply because they have a license to operate – and sometimes, they don’t even have that. There are countless stories of unlicensed technicians who know how to run measurement equipment and talk like a professional, who will perform a survey and have an actual licensed surveyor rubber-stamp a survey he or she didn’t supervise, performed by someone who isn’t his or her employee.

If we as professional surveyors don’t consider our work valuable, it will be all too easy for attorneys, architects, builders and others in the construction field to devalue it too.

Hard as it may be to believe, the concept of a licensed surveyor is actually fairly new. Although California passed the United States’ first licensure law in 1891, and Wyoming followed suit 16 years later, it wasn’t until the middle of the 20th century that every American state (plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico) had laws governing registration and licensing.

Now, professional licensing boards in each state uphold the public’s best interest by prohibiting fraudulent practice of surveying by non-professionals, and by holding licensed surveyors to rigorous education and experience standards.

The advent of licensing reflected the idea that a survey is more than a report in a stack of paper. It’s a professional service, the result of many hours of diligent, comprehensive work including land measurement, topographic maps, construction survey, and management of property documents and information to coordinate with local governance.

It takes a professional to do all of those things right. Just as accountants are entrusted with great monetary wealth, professional surveyors have their own fundamental mission: measuring, marking, and recording the fortune inherent in the land.